In my previous post “What’s Wrong with Democracy?”, I discussed reasons for the disgraceful apathy in the face of climate change, especially in the Anglophone democracies.

I suggested two reasons:

- Achieving the reductions in CO2 emissions would destroy the banking system due to massive write-off of fossil-fuel-dependent assets.

- Large reductions in CO2 emissions would conflict with the long-established social contract of affluence. This social contract rests on houses, cars, foreign holidays and cheap credit, a lifestyle mix that is inherently energy-intensive and wasteful. No affluent society has developed an alternative social contract.

Therefore only two outcomes can occur:

- Democracy changes such that a new social contract – compatible with a low-CO2-emission lifestyle – can develop.

- Global warming proceeds, with all the progressively destructive consequences. Ordinary people suffer, and in some cases die, while the powerful escape to havens least affected by climate change, at least to begin with.

In this post I will discuss Outcome 1. What form would democracy have to take to lead societies from wasteful, degenerate, abusive lifestyles to something better?

It first has to be said that the character of this new democracy would be that of a step-parent who has taken responsibility for a brood of thoroughly spoiled brats. The brats want to play with their motor cars – big, powerful motor cars weighing two tonnes or more with engines of 200 to 500 hp. The brats want to get on a jet and fly wherever they like, several times a year. They want to live in a roomy house, with a garden, in a suburb of low-density and they can’t be bothered with public transport. Only young people and plebs use public transport. Oh, and the brats want to eat lots of meat too.

The new democracy would also have to deal with the aversion of big business to reliance on rail transport. Since the 1960s there has been a general trend to road freight. This is less efficient than rail freight, cannot feasibly be converted to electric traction, and kills large numbers of MoPs (members of the public) every year. It greatly increases the costs of roads and bridges and the maintenance of said infrastructure. However, these costs are buried away in the public purse by conniving politicians, and so are not borne by the road haulage firms.

With all these factors against road freight, why is it that most freight goes by road? Because big business does not want to be hostage to the rail unions. Rather than bridge the social divide and develop a mutually dependent relationship, the boardroom class sends its freight by road, killing MoPs, burdening the public purse and clogging the roads. It does this because it is powerful enough to be able to do it. In any case, in the UK the Conservative party is essentially the public face of the boardroom class. Now, there are some less cynical, pragmatic reasons. It is obviously true that road freight is more flexible than rail. This does not justify the social and financial abuses inherent in road haulage as it is currently done.

There are more challenges for the new democracy. The public appetite for living now and paying later is inherent in a social contract based on houses, cars, foreign holidays and cheap credit. Citizens are encouraged into debt to raise the fixed costs of life, which in turn deters industrial rebelliousness. Life on credit is fundamental to the delusional nature of the affluent lifestyle. You can have it now without suffering the discipline of saving up. The easy provision of mortgage credit is fundamental to inflating house prices, which provide a sense of wealth to a population actually being held in debt servitude. However, easy credit promotes over-consumption. It destabilises the financial system. Over time, the debt accumulates and becomes dangerous (our current situation).

Let us take a moment to review this rather brief review of the challenges facing the new democracy:

- Concerning the general public: restrain car ownership and use, suburban sprawl, frivolous travel especially by air, and eating meat.

- Concerning the boardroom class: make road freight pay full economic cost and take full responsibility for its danger, exert preference for rail freight, ban consumer credit and limit mortgage borrowing.

Well, it looks like the new democracy would be confronting just about every vital aspect of consumer vanity and commercial expediency. Could this ever happen through a democratic process? It seems inherently unworkable that a democratically elected government could act against so many vested interests.

Now, it is not unknown for democratic government to defy the will of the people. A salient example is capital punishment, which was abolished in Great Britain in 1969, despite overwhelming public support for it. It is only in recent years, half a century later, that public opinion has shifted (possibly) to a slight balance in favour of abolition. This executive defiance of the will of the people could occur because of broad support across the major political parties. The debate for reintroduction of capital punishment was active up until the last vote in the UK House of Commons in 1994, with proposals repeatedly rejected (despite support from Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s).

That said, capital punishment is but one issue. Whereas, the challenges of dealing with climate change, debt and fossil-fuel dependency go to the root of the social contract of affluence. If we are to have a new kind of society, we must have a new social contract of affluence. Otherwise, we just ain’t going to have affluence for much longer.

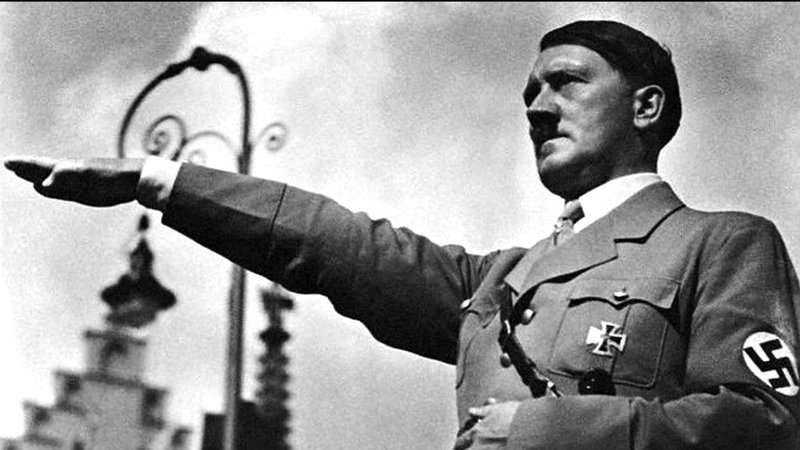

I believe that fear is the key to this. Unless climate catastrophe keeps people awake at night, there will not be the shift of mindset required to change the social contract. I am talking of a state of national emergency not seen since war broke out in 1939. Only then would the bickering political parties join in a coalition. Only then would the people be prepared to make the sacrifices required. I foresee the new social contract as having at best a grudging rather than enthusiastic basis. And it would not rest on much foundation. There would have to be a promise of a better tomorrow. If that better tomorrow did not come, then strife would follow.

Is this likely? As I write, vast tracts of Australia are burning. The smoke is circling the entire earth and coming back to its origin. The media are full of the ominous signs of climate change almost every day, and have been for years. Yet cheerleaders for the aviation industry continue to state as a matter of dogma that air travel will double in the next twenty years. The Conservative party of the UK won a large majority in the 2019 general election on a platform of doing virtually nothing about climate change, debt or oil dependency. What could a changing climate produce that would scare people enough to abandon their slovenly, comfortable ways? In my view, nothing. The climate is changing too slowly.

But there might be another way. It is not a nice way, in fact, it is a nasty way, but it could happen. This would be the coming to power of what amounts to a theocracy. In Saudi Arabia, gangs of bullies roam the streets beating people with sticks if they transgress (trivial) religious laws (they chop your head off if you break the big laws). The “envirocracy” would be something similar, a dictatorship of orthodoxy, but an orthodoxy of clean living rather than adherence to religious dogma. Private cars would be banned. Flying would be banned. Well, banned for the plebs, not for the high priests of this envirocracy, who would doubtless have their limousines and private jets. What changes? We’re all equal after all, it’s just that some are more equal than others.

You can doubtless now see why I have little faith in democracy saving the world from climate change. If climate change is to be averted, it will be due a social cataclysm that stamps out consumption. It is this deep pessimism that incited me to write the dystopian series Sovereigns of the Collapse.